The generosity of Ayn Rand

Critics of Ayn Rand have taken to claiming that she practiced and advocated an insular, vain, conceited, callous, narcissistic form of selfishness. Such critics seem to glance at the title of her book The Virtue of Selfishness and no more than skim the essays in which she specifies her reasons. The results are newspaper columns, blog posts, and book chapters which spread a viewpoint which is unmistakably wrong to those of us who know her actual views. Some people who enjoyed friendships with her have stepped forward to tell of Ayn Rand’s generosity, of her lavishing time to help them solve problems, and of financial assistance, as well. Ayn Rand was steadfastly moral about interacting with other people. She sought to trade, not necessarily through material values but often—perhaps most frequently—on the basis of values of good character.

What would most effectively dispel the charicature of Rand-as-conceited-solipsist is greater dissemination of facts which demonstrate that Ayn Rand supported her ideological opponents when she could gain sufficient spiritual value in return. The next two sections of this web page discuss Ayn Rand’s involvement with two organizations which mostly offered a platform for Ayn Rand’s political and philosophic enemies but which gave her an opportunity to speak to their audiences as well. Both organizations were beneficiaries of her helping them raise money to stay aloat.

Pacifica Foundation radio

Ayn Rand accepted invitations to speak over radio from the time she first drew public attention. New York theatergoers saw her play “Night of January 16th” during a six-month period of 1935-1936, and book readers across the United States were offered her first novel, “We the Living,” beginning April 7, 1936. Ayn Rand, then living in New York, went on radio a little more than a month after that publication date—May 18, 1936—to discuss Soviet Russia (which is the background of that first novel), a subject she knew from person experience. WEAF made the subject of its “Woman’s Review” program that day “Housekeeping Under the Soviets.” In a newspaper listing for that broadcast, “Ayn Rand, Author” is the only name listed for the particular broadcast, which ran from 4:00 to 4:15 p.m. over AM frequency 660.

During the 1960s, Ayn Rand would be heard on New York radio over WKCR-FM, WRVR-FM, WINS-AM, WNYC(AM/FM), and WBAI-FM. The WNYC broadcasts were limited to recordings of speeches delivered to auditorium audiences elsewhere. At WINS she spoke live to that station’s audience. WRVR carried a recording of a speech and had her once as an interview-show guest. (These last three statements are made on the basis of information I have, and may fail to take into account information unknown to me.) However, non-commercial stations WKCR and WBAI carried both (a) recordings of Ayn Rand speaking to a packed auditorium and (b) broadcasts which Ayn Rand made from these each station’s studio.

Ayn Rand’s having broadcast over WKCR for several years has been mentioned in some accounts of her. This was the station of Columbia University, and the station would have some of the university’s graduate students ask Miss Rand questions for the half-hour of a program. Some programs were Ayn Rand reading one or more of her essays for the length of the program. The views expressed by her in a program could then become the subject on which the PhD candidates would ask her questions in the subsequent program. Allan Gotthelf was one of these students, and later became a professor of philosophy who advocated for her philosophy. He also prepared indexes for her books. His recollections of her are published in the book 100 Voices: an Oral History of Ayn Rand (New American Library, 2010). He mentions his being with her at the WKCR studio on page 332 of that book.

The other of the two non-commercial radio stations—WBAI, operated by Pacifica Foundation—also had with Ayn Rand a relationship which lasted several years. It is also a fascinating relationship.

The relationship between Ayn Rand and Pacifica station WBAI will be told here through newspaper clippings. All of the clippings in this section are from The New York Times. Page numbers refer to the newspaper’s page numbers on the specific dates indicated.

|

On June 11, 1964, the station apparently broadcast Miss Rand’s speech “Is Atlas Shrugging?” The description (above, middle listing) leaves little other interpretation. Ayn Rand had delivered “Is Atlas Shrugging?” at the Ford Hall Forum in Boston on April 19, 1964, so it was a new speech at the time of this broadcast. (image from pg. 67)

May 11, 1965, had a half-hour of Ayn Rand in the early evening. (pg. 79)

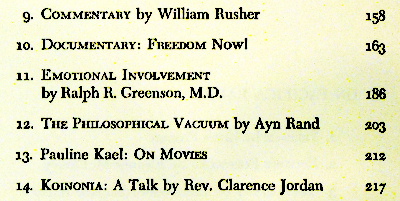

This January 13, 1966, listing has her again delivering “Commentary,” but now a half-hour earlier than before. (pg. 79) Brief background information about WBAI and the two other Pacifica stations operating at the time, can be found in the advertisement reproduced at right. The stations’ basic operating motivation is easily gleaned. Reading to the bottom of this ad—which ran June 26, 1966 (pg. 12)—one finds that Pacifica compiled a book from material broadcast over its airwaves. Reading further, one finds that among the authors was Ayn Rand. (Also named is Erich Fromm, whose book The Art of Loving was dissected and refuted in an essay (by an Objectivist other than Ayn Rand) in her book The Virtue of Selfishness.)

The Pacifica Foundation book The Exacting Ear was published by Pantheon in May 1966. The New York Times reviewed the book in its July 3, 1966, issue (pg. 141). The section of the review shown below names the stations operated by Pacifica Foundation and names two of the commentators whose voices and views were heard on the station; one of them is Ayn Rand.

(Station KPFK in Los Angeles, also named in the ad and the review, had in the early 1960s broadcast Ayn Rand talks, including “Is Atlas Shrugging?” on July 1, 1964.) |

|

right: WBAI has—as have so many other broadcast outlets supported by their audiences—used its air-time to ask its listeners to provide financial support to it. A May 2, 1967, Times story (pg. 94) reports on the fundraising effort then underway. Ayn Rand is named as among those who would be heard on the station during the fundraising period.

above: A month after the beginning of the fund drive, the station set aside two hours on a Sunday evening—June 4, 1967—to carry Miss Rand’s appearance at the Ford Hall Forum (in Boston) on April 16 of that year. (pg. X22) Two hours is time enough to broadcast both the lecture and question period. |

|

Here opens “The Exacting Ear.”

|  | |

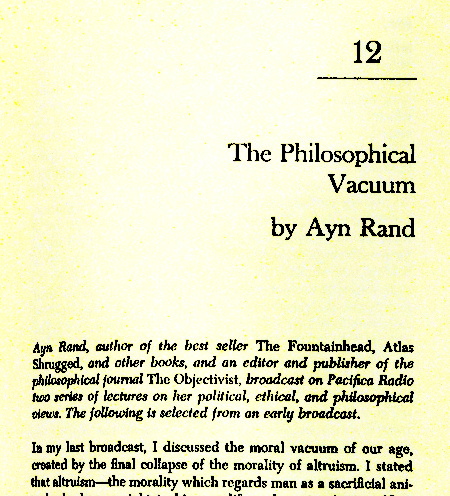

The book provides a respectful introduction about Ayn Rand. The editorial remarks don’t state the essay broadcast date, only that it was “early” in Ayn Rand’s association with Pacifica. The essay covers a gamut of philosophic subjects—altruism, pragmatists, logical positivists, perception, academia—and thus is similar in comprehensiveness to some of Ayn Rand’s earlier writings for The Objectivist Newsletter (begun 1962). (Later, her non-fiction had narrower scope in each writing.) Although this article discusses the same subjects which Ayn Rand did in some of her other writings of the time, this is an entirely different article from any published in any of Ayn Rand’s periodicals. She did not include this article in any of the anthologies she prepared from her writings, and in the years since her death, her estate and its authorized organizations have not reprinted it either. This article has remained exclusive to the book published by Pacifica Foundation (long out-of-print). |  |

Pacifica Foundation filed the copyright on the book, giving the date of publication as May 26, 1966, and on the registration form made this statement regarding any limitations on their claim of copyright: “Copyright is claimed in all matter except FCC decision and Chapter 17, ‘From an Autobiographical Novel by Kenneth Rexroth’.” If this is correct, then Pacifica obtained copyright from Ayn Rand, and any new effort to reprint the article by Ayn Rand’s estate, Leonard Peikoff (her legal heir, and legal successor to her estate), any successor to Peikoff, any publisher associated with any of the previous, or any publisher acting on his own, would have to arrange clearance through Pacifica.

Leonard Peikoff—who knew Ayn Rand during this entire period—would say on a commercial-station live radio broadcast that Pacifica radio had invited him to speak, thereby showing that even when they could not get her (she was long-dead then) their people were not all left-wing. The caller he was responding to had said that evils were communicated over the air on Pacifica radio. Peikoff said that they used to have Ayn Rand on the air as “window dressing,” which I interpret as a way of saying that they were disguising at first glance what they were at their essence. (“The Leonard Peikoff Show,” KIEV radio (AM 870), Los Angeles (Calif.), February 2, 1996.) Until the Federal Communications Commission removed the Fairness Doctrine in 1987, broadcasters who covered controversial issues were required to cover all sides of those issues. Having Ayn Rand broadcasting may have been a means by which Pacifica radio intended to fulfill that requirement. Pacifica’s alternatives would have been to mute their left-wing voices or face an F.C.C. action to cancel their broadcasting license.

The Ford Hall Forum

The Ford Hall Forum has been mentioned above as the venue from which Ayn Rand delivered speeches in 1964 and 1967. Ayn Rand gave her first speech at the Ford Hall Forum on March 26, 1961, and returned December 17 the same year. A speech almost exactly a year later—December 16, 1962—would be followed by one sixteen months later, on April 19, 1964. She gave one speech there each year thereafter, from 1965 up to and including 1974. Four speeches were delivered after that, sometimes at annual increments, sometimes less frequently. The last was in 1981.

The Ford Hall Forum program was heavily imbalanced in favor of left-wing speakers when Ayn Rand first received an invitation. Two decades later, following her death, when Leonard Peikoff spoke from the podium at what would have been Ayn Rand’s appearance had she not died, he told the audience of her high regard for the Ford Hall Forum. She at first did not know whether the Ford Hall Forum would be an appropriate venue for her, but learned that she would be treated fairly. The Forum’s pledge to offer viewpoints from all sides was not a false claim for them, as it was when claimed by other organizations. Leonard Peikoff said that Ayn Rand considered the Forum honest. (He stressed this last word.)

In 1999, a woman who had worked at the Ford Hall Forum in 1961 answered questions about Ayn Rand’s association with the Forum. Asked how Ayn Rand came to be invited the first time, Frances Smith responded, “The program committee at the time found that as we looked over the programs for a number of years that we were really overloading the programs with left-wing people giving talks, and we felt that it wasn't a good, balanced program, which is what we wanted to present. So the committee sought somebody who was of a more conservative nature who would be interesting enough to draw an audience, and that’s why we asked her.” (Frances Smith interviewed by Scott McConnell in 100 Voices: an Oral History of Ayn Rand (New American Library, 2010), pg. 222.)

Ayn Rand’s connection with the Ford Hall Forum is here told largely through clippings. All of the clippings in this section, except for the last, are from the Boston Globe. Page numbers refer to the newspaper’s page numbers on the specific dates indicated.

right: Under the headline “Socialism Brain-Killer —Ayn Rand,” the April 20, 1964, Boston Globe (pg. 34) began a three-paragraph story by stating, “Novelist Ayn Rand said Sunday that demands of socialistic government are forcing the best minds of America and the world to abandon their work”. The second paragraph is reproduced here. |

|

Miss Rand’s 1966 appearance

This ad appeared April 9, 1966 (pg. 22), the day prior to the event; the same ad also ran April 8 (also pg. 22). |

On the day of the event, the April 10, 1966, Globe (pg. A33) carried this announcement. |

| A well-illustrated, multi-page article about the venue—titled “1908-1968: Ford Hall Forum: Boston at Its Best”—in the December 15, 1968, issue (pg. A6) told in its third paragraph that organizers knew Ayn Rand would draw a huge crowd. (The first three paragraphs of the article are reproduced here.) |

Ayn Rand’s 1969 speech has always been published by the title “Apollo and Dionysus,” but here two parenthetical additions are included. That “Woodstock” is the boldest word is fitting for an effort to draw a crowd, as the concert was a cultural touchstone of the time. The advertisements directly above and below reflect the new indulgence. Advertised elsewhere on the page was a play about J. Robert Oppenheimer, the atomic-bomb scientist whom Ayn Rand drew on in devising the character of Dr. Robert Stadler. From the November 8, 1969, issue, pg. 20. |

|

Financial difficulties threaten the Ford Hall Forum

| This story from May 20, 1971, reports on a dinner at which Ayn Rand was among the speakers who gathered for the purpose of raising money for the Forum. (pg. 53) In 1971, the $50 cost of attending would have bought 136 gallons of gasoline, 94 boxes of a dozen eggs at retail, or 32 ounces of silver. |

The financial difficulties of the Forum recurred two years later, when this article discussed the venue’s past. (The news story was reported in the same size typography throughout its body, but for this web page the part related to Ayn Rand has been made bigger; that larger-type content at the bottom of the image is from near the end of the full story. Parts irrelevant to Ayn Rand have been omitted from the image.) From the September 13, 1973, issue, pg. 3.

This news story was fresh in the minds of many Boston residents when Ayn Rand next appeared at the Forum: October 21, 1973. The second question posed to Ayn Rand by a member of the audience during the question period concerned Miss Rand’s remuneration for her speaches at the Forum. As was his custom, Forum moderator Judge Reuben L. Lurie repeated the question—here, with his own interjection—for the benefit of audience members who had been unable to hear the question delivered from within the large audience section of the hall: “perhaps Miss Rand knows what you already know because of my constant appeals, of the financial difficulties of the Forum, and part of the reason for the financial difficulties of the Forum derives from the fact that the fees charged by speakers have grown really quite enormously, and [addressing Ayn Rand] you on the other hand have been a constant friend of the Forum and have not sought to take advantage of this, and he regards this as an interesting paradox, since he would say that this is altruism, and he wonders what your defense of this is.”

Miss Rand’s answer should be mandatory listening or reading (if there could be “mandatory” content) for anyone who expresses a position on the terms by which Ayn Rand contracted with others. She told the questioner and the audience at the Forum: “First of all, how do you know what values speakers charge? I’m not going to tell you, but if the judge is willing, I will ask him later, after I answer, to answer you on that point. But the main point in your question is that you assume that the only possible values one can derive from any activity are financial, therefore that anyone who wants to be a speaker does so only for a very high fee. Well, you know, that is placing your self-interest terribly low, and terribly cheap. It’s a very difficult job which no one who wants to do it for money should undertake, because too much work is involved—you wouldn’t make a fortune that way. Well, then what’s my point, my purpose? Altruism? No! In any deal, you—[correction:] In a proper deal—you act on the trader principle. You give a value, and you receive a value. Your question would imply that unless I collect some kind of fortune, which I don’t need—I’m collecting it in other ways, incidentially—unless I am paid, I have no interest in spreading ideas, which I believe to be right and true, that the only purpose is to enlighten others. That would mean that I have no interest in a free society, that I have no interest in denouncing the kind of evil which I can see and want to speak against—that all that is not to my selfish interest, it’s only to the interest of my audience and not to mine; that would be an impossible contradiction. If I believed it, I wouldn’t be worth two cents as a speaker. I believe that I have the most profound and the most selfish interest, in having the freedom of my mind, knowing what to do with it, and therefore fighting to preserve it in the country, for as long as I’m alive, or even beyond my life. (I don’t care about posterity, but I do care about any free mind or any independent person who may be born in future centuries—I do care about that.)”

Ayn Rand made the above remark extemporaneously in the question sesssion following her speech “Censorship: Local and Express.” Those wanting to hear her speak the answer, or want to check the wording transcribed here, can acquire the audio online for under a dollar (at the time of this writing). Both the speech and the Q&A session are offered together in separate audio files. The specific question of the speaker fee occurs about two minutes into the Q&A session. Click here to be taken to a page on another domain where the purchase can be made. Note: For several years, the audio of all of Ayn Rand’s Ford Hall Forum sessions could be streamed for free at the Ayn Rand Institute’s Multimedia Library, but this feature was apparently removed prior to the creation of the present web page.

| This news account of Ayn Rand’s 1974 appearance was published the following day, October 21, 1974 (pg. 5). Her popularity remained considerable. The story concluded by stating that the speaker the next week would be Ralph Nader. Ayn Rand made a critical remark about Nader in her October 20 speech. Her comments about Nader in “Egalitarianism and Inflation,” were not her first. Previously, she had identified Nader as belonging to bad political trends in the issues of her The Ayn Rand Letter dated April 23, 1973 (“Brothers, You Asked For It!”), and November 19, 1973 (“The Energy Crisis”). |

The Ford Hall Forum after Ayn Rand’s death

The following news clipping is the one in this section not from the Boston Globe.

Following Ayn Rand’s death, the Christian Science Monitor mentioned her in a profile of the Forum published in its May 20, 1982, issue, pg. 7. Ayn Rand’s choice to keep her speaking fee low and to forego perks is recounted as though an exception among speakers; the policy is consistent with her willingness to support the institution which had helped her by giving her a place to voice her views to an audience that otherwise may have never heard them.

The Norman Lear mentioned here was founder of People for the American Way, which Ayn Rand criticized in her last-ever speech owing to the group’s ineffectual, anti-philosophical television commercial. Miss Rand delivered that speech elsewhere in 1981, and was scheduled to deliver it at the Ford Hall Forum on April 25, 1982. Leonard Peikoff delivered it in her stead. (The text of the speech does not identify the group’s name exactly, but her description of the television commercial makes it clear that it is the same group for those of us who saw the commercial repeatedly in its time. Lear is not named in Rand’s remarks nor was his involvement evident from the commercials.) The speech, “The Sanction of the Victims,” is published in The Objectivist Forum periodical and bound volume, and in the anthology book The Voice of Reason.

Note: the gray squiggly line indicates where the first portions of the article have been omitted here, and the bottom part of the first column moved up. (The second column starts the same way in the original as it does here.)

Summary statements about Ayn Rand’s experiences with Pacifica Foundation and the Ford Hall Forum

• Ayn Rand went on-air at the New York station of Pacific radio while the station was raising funds from its audience to continue offering programming which was mostly left-of-center.

• Ayn Rand wrote an essay which she not only delivered over-the-air, but which went on to be published in a Pacifica book and in no other source.

• Ayn Rand kept her speaking fee at the Ford Hall Forum at the same amount while other lecturers were raising theirs to ten-fold the prior norm.

• Ayn Rand spoke at a dinner where the Ford Hall Forum raised money to continue its operations.

People who knew Ayn Rand

Many, many people whom Ayn Rand befriended or knew her through work or acquiantance, have shared their stories and impressions about Ayn Rand in interviews. Transcribed, these interviews have been published in Facets of Ayn Rand (memoirs of Mary Ann Sures and Charles Sures, published 2001) and 100 Voices: an Oral History of Ayn Rand (a hundred people whose reminiscences were transcribed by Scott McConnell, published 2010). The introduction to the book of the Sureses’ reminiscences states that it “offers plentiful examples of Ayn Rand’s mind, and intellectual generosity, in action, and also captures many lesser known aspects of this unique woman.” Both books ample evidence of Ayn Rand providing aide, comfort and wisdom, demonstrating too that she conceded that another person had a point in valuing something they did, even when Ayn Rand did not share an estimate (for example).

In her personal relationships as at the Ford Hall Forum, she had an “interest in spreading ideas, which I believe to be right and true,” in achieving “a free society, […] in denouncing the kind of evil which I can see and want to speak against”. In a 1972 essay, she recognized that achieving that ideal society was a very large job: “No one can change a country single-handed.” She compared her approach to being “a doctor in the midst of an epidemic. You would not ask: ‘How can one doctor treat millions of patients and restore the whole country to perfect health?’ You would know, whether you were alone or part of an organized medical campaign, that you have to treat as many people as you can reach, according to the best of your ability, and that nothing else is possible.” (“What Can One Do?,” in The Ayn Rand Letter, January 3, 1972)

New content © 2014 David P. Hayes