Ayn Rand advocated for a law permitting abortion when few U.S. states allowed it

She followed news on the incremental changes which increased Americans’ rights on abortion starting from 1967

Ayn Rand often wrote that attempting to attain a desired government policy on the basis of bad arguments would lead to the policies self-destructing in practice. Such an attempt was pragmatism, and offered many arguments demonstrating that pragmatism leads to failure. However, on one desired policy change, she advocated for supporting already-percolating efforts toward the same overall goal, acknowledged the lack of the recognition of a moral right as a defect in the mainstream efforts, but nonetheless urged her readers to embrace the emerging trend and available option as “a great step forward.”

In this instance, she wrote that the proposal was one “we can support without supporting a number of dangerous contradictions at the same time.”

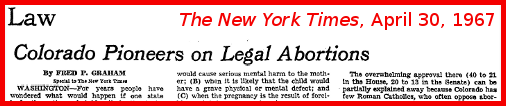

The subject of that change was on abortion. The place and time were the United States in the 1960s. Ayn Rand followed the news on changes in law. During that decade, many Americans undoubtedly realized that a shift in public sentiment about abortion laws was beginning. In Spring 1967, they encountered news items such as this one:

“Last week Colorado enacted the most permissive abortion law in the nation’s history—a law so liberal that a cry went up from its opponents that the state would become an ‘abortion mill’ for the rest of the country.” (Fred P. Graham, “Colorado Pioneers on Legal Abortion,” in The New York Times, April 30, 1967. The selection quoted here was the full text of the third paragraph of the article; it is also the fourth sentence of the article.)

The article reports further:

In 45 states, doctors may legally perform abortions only to save the life of the mother. Four other states—Alabama, Maryland, New Mexico and Oregon—and the District of Columbia also permit abortions to preserve the mother’s health.

Colorado’s new law permits abortions in these situations and also (A) when the birth would cause serious mental harm to the mother; (B) when it is likely that the child would have a grave physical or mental defect; and (C) when the pregnancy is the result of forcible statutory rape or incest.

The “abortion mill” charge came up owing to concerns that “large numbers of women [may] succeed in having pregnancies terminated on ‘mental impairment’ grounds, simply because they don’t want the children. The law requires a psychiatrist’s certificate of probable ‘mental impairment,’ and nobody knows how freely these will be given.” (Quotation from the same article)

A little over two months prior to the Colorado enactment, the same newspaper indicated that efforts were under consideration in New York State, where Ayn Rand lived. An article in the Times began: “Hearings have been held these last weeks about the proposed liberalization of the New York State Abortion Law in the form of a bill proposed by Assemblyman Albert H. Blumenthal.” After the article outlines the scope of the debate, the third paragraph of the article states: “It is now mainly the Catholic Church which wishes to maintain the punitive measures of the 84-year-old New York State Abortion Law, and its reason is in terms of its dogma.” (Marya Mannes, “Topics: On the Casting of Stones,” The New York Times, February 18, 1967)

Ayn Rand kept a clipping of each of these two New York Times articles in a file folder of hers. (I know this from the Ayn Rand Archives having assembled an exhibit at an OCON Objectivist Conference wherein the archivists displayed Miss Rand’s clippings, each adorned with Miss Rand’s hand-made markings.)

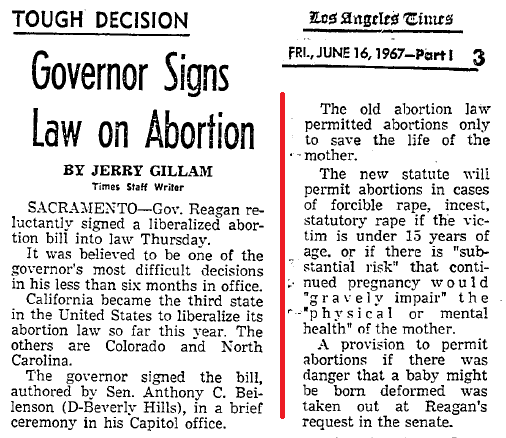

Before New York State came to change its abortion law, North Carolina and California had followed Colorado to enact abortion laws considered exceptionally permissive at the time. The revision in California was a month and a half after that of Colorado. The New York Times summarized the California law: “The statue legalizes abortions when the child’s birth would endanger the physical or mental health of the mother, in cases of statutory rape involving a girl under 15 years of age, and when pregnancy resulted from forcible rape or incest. The law will replace one that permits abortions only to save the mother’s life.” As with the Colorado law, “The California law has no residence requirement.” (“Reagan Reluctantly Signs Bill Easing Abortions: California Becomes 3d State to Liberalize Curbs — Law’s Effect Delayed,” sourced from UPI, in The New York Times, June 16, 1967)

I reproduce below two excerpts from the report that appeared in the largest-circulation newspaper in that state on the day after the signing into law of this legislation. I will refer to those excerpts in my next remarks, so I suggest you read the text in the image before continuing to read my commentary below the image.

To modern readers, the governor’s extracting a concession against the inclusion of a deformed fetus to be considered among justifications allowing abortion, may seem draconian. However, at the time, the law as passed, taken as a whole, was a significant advance in abortion rights. What’s more, the final version would not preclude a woman with a deformed fetus from seeking and obtaining a psychiatrist’s certification that this pregnancy would harm her mental health, thereby allowing an abortion on that ground. Reportedly, within the state capitol, persons on both sides of the issue understood that the “mental health” exception would lead to women sharing information as to which psychiatrists would reliably issue certifications after a single therapy session. Nonetheless, by having decisions made by psychiatrists, politicians could plausibly claim denial about results which would alarm some constituents.

Reagan would later present himself as having governed California from an anti-abortion standpoint, yet the contemporary reports indicate otherwise. A California governor, like the president at the federal level, can veto bills from the legislature, after which passage is blocked save for the veto being overridden on a legislature vote with a two-thirds majority. The California abortion legislation had passed the state Assembly by a 48-to-30 vote and the state Senate 21 to 17, so it would likely have failed on an override attempt. Whatever may be thought of Reagan’s stated positions on abortion, he did allow access to abortion to expand in California under circumstances where he could have kept the prior severe restrictions.

Three days after reporting on the new law in California, The New York Times began an article with: “California and Florida are the latest states to take steps toward sweeping away some of the cruel and archaic legal barriers to abortion.” After summarizing again the California law, the Times stated, “Florida’s Senate has approved similar legislation.” (“Abortion Reforms—Elsewhere,” in The New York Times, June 19, 1967)

New York State did not revise its abortion law during the remainder of 1967 nor in 1968. Ayn Rand, writing in the February 1969 issue of The Objectivist, reported, “The New York State Legislature is considering the matter of reforming and liberalizing the present abortion law. The present law, which has not been changed in 86 years, is an inhuman statute that forbids all abortions except when the mother’s life is in danger.” She went on to write:

A proposed abortion-law reform was defeated in the State Legislature last year. Now, it has been brought up again and there is a good chance that it will be passed—if the voters support it and make their views known.

The change in the legislators’ attitude was caused by the fact that polls taken after last year’s defeat indicated that a majority of the people favor reform.

Here is a clear instance of how political evils are brought about or perpetuated by default. There is only one major pressure group that opposes reform, the group responsible for the existence of laws forbidding abortion and contraception: the Roman Catholic church. [...]

Governor Rockefeller, who favors the abortion-law reform, has said in regard to the prospects for reform this year: “I think it’s possible, and particularly if the public lets the Legislature—or their representatives—know their feelings on the subject.” (The New York Times, January 15, 1969.)

A consistently proper stand on this issue would require the total repeal of the law forbidding abortion. This is not likely to pass at present, but the kind of amended laws that have been proposed would represent a great step forward, would save many lives and alleviate an incalculable amount of human suffering—provided they include a clause which permits legal abortion when the pregnancy endangers a woman’s physical or mental health. Such a clause would protect a woman from lifelong despair and would give her a chance to assert her rights.

A news story in The New York Times (January 30, 1969) said: “The provision about mental health is particularly significant because opponents of abortion-law change, led by the Roman Catholic bishops of the state, have argued that this would allow women with unwanted pregnancies to obtain legal abortions simply by attesting that they were distraught about having the child.” Yes, of course. That is the point. (Judge for yourself the motives—and the humanity—of men who would raise an objection of that kind.)

[...]

There are few political actions today that we can support without supporting a number of dangerous contradictions at the same time. The abortion-law reform is one such action; it is clear-cut, unequivocal and crucially important. It is not a partisan issue in the narrow sense of practical politics. It is a fundamental moral issue of enlightened respect for individual rights versus savagely primitive superstition.

Therefore, I urge our readers in New York State to write to the State Legislature, expressing their views on this issue—and to do it as soon as possible, because the matter will come to a vote in the very near future.

If you agree with me, I suggest that you state, briefly, your conviction that abortion is a woman’s right and your opposition to any reform bill that would omit the clause protecting a woman’s mental health.

She went on to state where to send letters and to whom they should be sent.

(Quotation from: Ayn Rand, “A Suggestion,” in The Objectivist, February 1969)

Governor Rockefeller signed a new abortion law on April 11, 1970, a day after the state Senate passed it. Elective abortions were legalized through the 24th week of pregnancy; abortions in subsequent weeks of pregnancy were allowed when it was to preserve the woman’s life.

Less than three years later, the United States Supreme Court issued its Roe v. Wade decision, which legalized abortion in every U.S. state and territory. The Court recounted then-recent changes in laws in states other than the one where the petitioner lived, stating: “In the past several years, however, a trend toward liberalization of abortion statutes has resulted in adoption, by about one-third of the States, of less stringent laws”. In a footnote, the Court mentioned a resource “listing 25 States as permitting abortion only if necessary to save or preserve the mother’s life.” This changed with the Court’s decision.

For decades after that, a woman’s legal right to abortion without requirement that her reason be acceptable to anyone else (provided the abortion be performed within time limits established by reference to medical considerations), was commonly understood as normal. Whatever annoyance Miss Rand may have had concerning the New York State provision that a woman declare that she would be distraught were she denied an abortion, that New York law had been part of an incremental change which soon brought about a clear decision that women were to answer to no one else regarding that right.

Sidebar: Reagan role has been distorted in later re-tellings

In offering the selection of paragraphs that I included in the image from the June 16, 1967, Los Angeles Times reporting on Reagan’s signing the abortion law, I seek to dispel revisionist distortions about how the legislation became law. There have subsequently been falsifications asserted by both latter-era allies and foes of the state’s governor of the time.

The illustration with two excerpts is just 56 kb in size and 506 pixels wide, so it can easily be saved to re-use when engaged in online debate with someone misreporting then-Governor Reagan’s actions. Feel free to re-use it with my compliments; there’s no need to credit me.

Whatever you think of Reagan, I hope you share my belief that the reporting of history should be accurate.

Sidebar: Nelson Rockefeller

If you read my web page cataloging Ayn Rand’s endorsements in presidential races, you may remember that she was opposed to Nelson Rockefeller getting the Republican nomination. In her remarks reproduced on the present page, she factually reports on Governor Rockefeller in a way that demonstrates that he and she were on the same side on the issue of abortion. Given the context in which she provides one quote from Rockefeller, we may surmise that Miss Rand wanted her readers to follow his advice in that quote that her readers send letters to their representatives. We know that Miss Rand had disagreements with Governor Rockefeller on some matters, but that didn’t prevent her from joining him on an ad hoc basis.

Those who would like to make another visit to my page of Ayn Rand presidential endorsements — or their first visit — will find it at https://dhwritings.com/AynRandLinks/AynRandEndorsementsForPresident.html

Sidebar: similar passages between two authors

In the February 18, 1967, item in The New York Times quoted above, an item that Ayn Rand kept and marked much of, author Marya Mannes wrote: “no responsible medical or psychiatric organization has found that either fear of pregancy or of birth out of wedlock has in any way acted as a deterrent to premarital sexual relationships.” (The article appears under the title, “Topic: On the Casting of Stones.”)

Ayn Rand in her speech “Of Living Death” said that a then-recent papal encyclical “states that ‘artificial’ contraception would open ‘a wide and easy road toward conjugal infidelity.’ Such is the encyclical’s actual view of marriage: that marital fidelity rests on nothing better than fear of pregnancy. Well, ‘not much experience is needed in order to know’ that that fear has never been much of a deterrent to anyone.”

(Speech given at The Ford Hall Forum, Boston, on December 8, 1968; published in The Objectivist, issues dated September, October and November 1968, which were published in December 1968 and January 1969, owing to a delay in the publishing schedule. Six years after Ayn Rand’s death, “Of Living Death” was reprinted as chapter 8 of the anthology “The Voice of Reason.”)

Miss Rand’s remark “that fear has never been much of a deterrent to anyone” is quite similar to Mannes’s declaration that “fear of pregancy or of birth out of wedlock has [not] acted as a deterrent to premarital sexual relationships.” Given that Rand read Mannes’s essay, might the latter have informed her view, added evidence to her premises, or bolstered her resolve that this point should be incorporated into the limited time of her speech?

New content on this page

© 2024 David P. Hayes